Gaussian Mixture VAE

Not too long ago, I came across this paper on unsupervised clustering with Gaussian Mixture VAEs. I was quite surprised, especially since I had worked on a very similar (maybe the same?) concept a few months back. It’s an interesting read, so I do recommend it. But the basic gist of it is: instead of a typical VAE-based deep generative model with layers of Gaussian latent variables, the authors propose using a mixture of Gaussians for one of the layers. In doing so, we can now do unsupervised clustering with the new Gaussian Mixture VAE (GMVAE) model.

There are two parts of the paper that I wish to address. First, I don’t like the name: Gaussian Mixture VAE. Second, I am concerned with their interpretation that the Consistency Violation term fixes an “anti-clustering” effect induced by the categorical variable prior. This post is mostly dedicated to the second concern.

GMVAE Is Not Actually A GMVAE

One thing that bugged me was that they didn’t actually have a mixture of Gaussians per se. In their paper, they used the following generative model

\[\begin{align*} p(x, y, z_1, z_2) &= p(y)p(z_2)p(z_1 \mid y, z_2) p(x \mid z_1)\\ y &\sim \text{Cat}(1/K) \\ z_2 &\sim \mathcal{N}(0, I) \\ z_1 &\sim \mathcal{N}(\mu_z(y, z_2), \sigma_z^2(y, z_2))\\ x &\sim \mathcal{B}(\mu_x(z_1)), \end{align*}\]I should note that my naming choices differ from theirs and is more in keeping with previously established naming convention. Anyway, the authors noted that \(Z_1\vert Z_2\) is a Gaussian mixture, which inspired the name GMVAE. But once you marginalize out \(Z_2\), the distribution in \(Z_1\) is actually an arbitrary distribution thanks to the non-linearities in the \(\mu_z(\cdot)\) function. So what they really have is a mixture of arbitrary distributions in the space of \(Z_1\). I think the naming convention is a bit unfortunate, but I can also see why they chose it. But in any case, at least it’s still a mixture of distributions!

The Prior Is Anti-Clustering?

In order to perform clustering well, the authors made an eyebrow-raising modification to the standard variational objective. In particular, they introduced a new \(\eta\) term. For the generative model mentioned above, the variational lower bound of \(p(x)\) is

\[\begin{align*} \mathcal{L} &= \E_{q(y, z_{1:2} \mid x)} \brac{\ln p(y)p(z_2)(z_1 \mid y)p(x \mid z_1) - \ln q(y, z_{1:2} \mid x)}\\ &= \E_{q(y \mid x)}[\ln p(y) - \ln q(y \mid x)] + \text{more terms}\\ &= -KL(q(y \mid x) \| p(y)) + \text{more terms}. \end{align*}\]With a bit of refactoring, you will find that the lower bound can be re-expressed to show the effect of the KL-divergence between \(q(y \mid x)\) and \(p(y)\). The argument goes: since \(q(y \mid x)\) is forced to be close to the prior, the KL-term has an anti-clustering effect and thus needs to be down-weighted by some factor \(\eta\) during training.

The authors also introduced a new auxiliary objective: the Consistency Violation term. To greatly gloss over the specifics, this term minimizes the conditional entropy \(\mathcal{H}(Y \mid X)\). The upshot is that \(\eta\) and CV are both modifications to the original variational objective in order to counteract the nefarious anti-clustering prior.

I can understand this line of logic, but I also think sends the wrong message about the purpose of the prior. Saying that the prior is anti-clustering is a bit of a deepity. From a different perspective, the prior is doing exactly what it is supposed to be: be anti-informative. The prior encourages \(X\) to not encode information into \(Y\) because doing so incurs the KL penalty. But suppose that encoding into \(Y\) helps improve reconstruction. If the reward of better reconstructions outweighs the cost of the incurred penalty, then the model will use \(Y\).

The M2 Model

The big question is then: does using the discrete \(Y\) actually help improve the variational lower bound? In other words, does encoding into \(Y\) help more than it hurts? Intuitively, the answer seems to be yes—for the right type of data. In MNIST, for example, there are very clearly 10 different classes. It seems natural that an optimal encoding will involve a categorical variable.

It would be nice to know, without all the bells and whistles of weighting terms and Consistency Violation, how well a mixture VAE trained using the vanilla variational objective would perform as a clustering algorithm. Fortunately, the paper does provide such an example in Figure 2d. However, they did not provide a quantitative measure of how well the model would perform on the MNIST unuspervised clustering task. More importantly, they are training their 2-stochastic-layer model using mean-field approximation. It is notoriously difficult to train Deep Latent Gaussian Models (DLGMs) when you restrict the variational family to the set of independent Gaussians, and a lot of work had been done to find better ways of doing structured mean-field inference.

In order to not potentially conflate multiple contributing factors, let’s make our experiment as thorough as possible and revisit Kingma’s M2 model. In Kingma’s original semi-supervised learning paper, Kingma proposed a simple generative model of the form

\[\begin{align*} p(x, y, z) &= p(y)p(z) p(x \mid y, z)\\ y &\sim \text{Cat}(1/K) \\ z &\sim \mathcal{N}(0, I) \\ x &\sim \mathcal{B}(\mu_x(y, z)). \end{align*}\]As far as mixture VAEs, this is probably the simplest one. Furthermore, M2 was successfully used for semi-supervised learning, so it is a bit unfortunate that the GMVAE authors did not evaluate the performance of unsupervised M2. So that’s what I did.

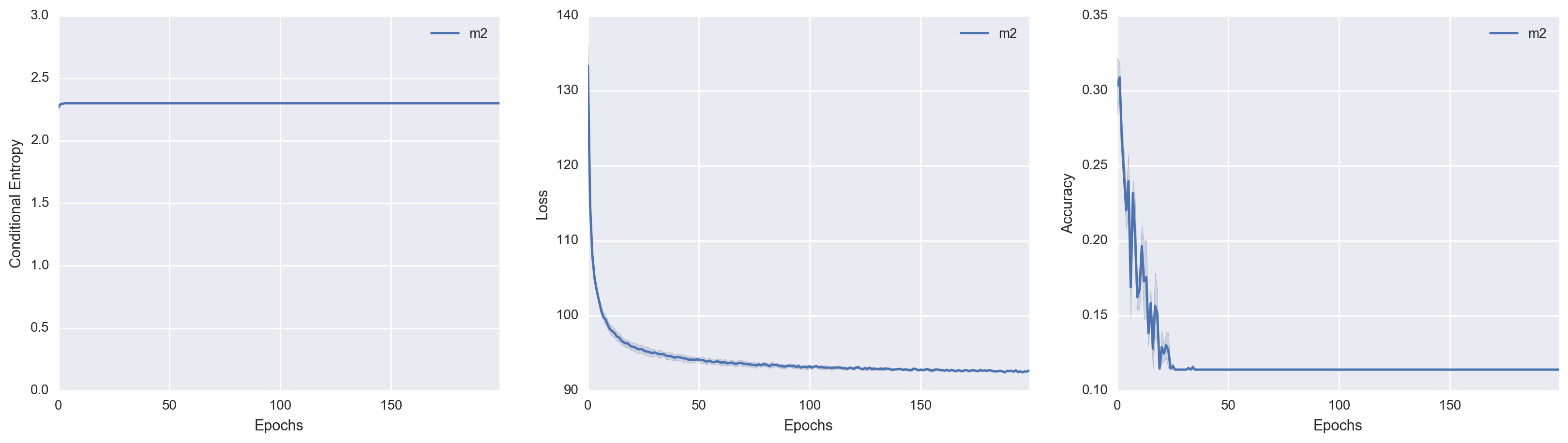

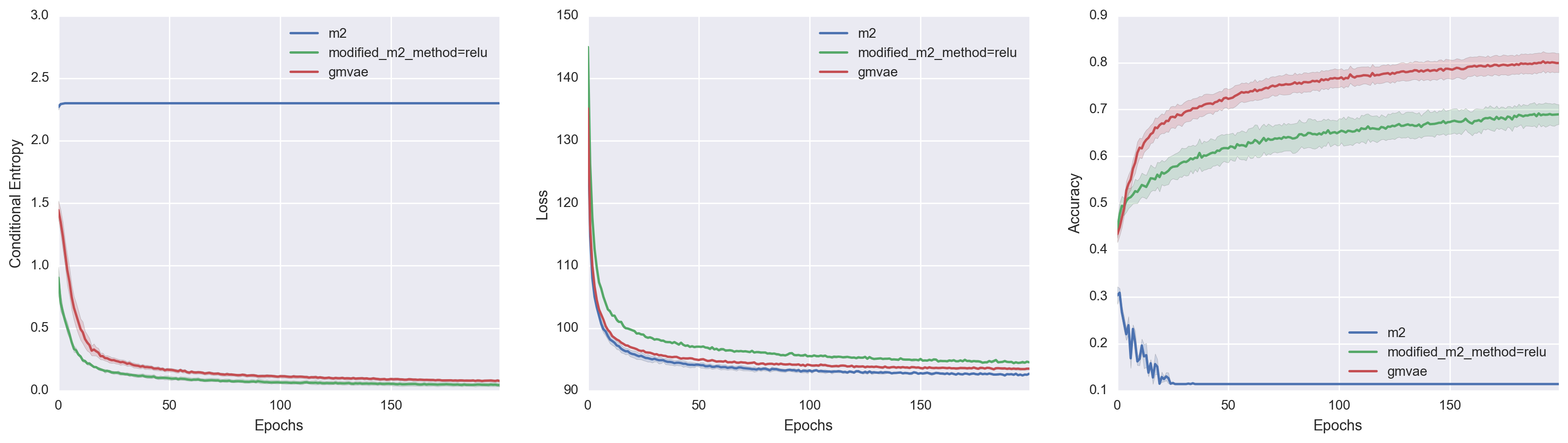

I trained M2 on the MNIST data set in an unsupervised manner. During training, I kept track of the conditional entropy \(\mathcal{H}(Y\mid X)\), the variational loss (which I define to be the negative variational lower bound), and the cluster accuracy. The cluster accuracy metric is defined in section 4.2 of the GMVAE paper: we assign the class label to the cluster based on the most-frequently-occuring label within a cluster. The test set performance over time for each metric is shown respectively.

The results are horrifyingly dismal. It is quite remarkable to see just how poorly M2 performs at unsupervised clustering! In fact, it is painfully obvious that \(Y\) was not used at all. The conditional entropy indicates that \(q(y \mid x)\) is a uniform distribution. The Accuracy v. Epochs plot is most striking: at some point, \(Y\) was in fact encoding the class label information of \(X\) (to some extent), but then proceeded to give up on this endeavor entirely.

So Why Did The Model Fail?

Note: I no longer subscribe to the explanation given in this section

To some extent, yes, the “anti-clustering” prior obviously played a role. But that is not a satisfactory explanation, because the question still remains: why on earth wasn’t it useful to encode information about \(X\) into \(Y\)? Even if the mutual information between \(Y\) and \(X\) is maximal, we would only incur a penalty of \(\sim2.3\) nats. One would imagine that correctly realizing that there are actually 10 different manifolds in the data-generating distribution is worth more than \(2.3\) nats.

I have a hunch as to why the model failed. If you pay close attention, you will notice that the marginal distribution of \(Z\) in the inference model is

\[\begin{align*} q(z \mid x) &= \sum_i q(z, y \mid x) \\ &= \sum_i q(y \mid x) q(z \mid x, y). \end{align*}\]Recall that we are using independent Gaussians as our variational family. If our model reduces the conditional entropy \(\mathcal{H}(Y \mid X)\) to zero (i.e. maximal mutual information \(I(X, Y)\)), \(q(z \mid x)\) reduces to a Gaussian. But if \(Y\) is not informative about \(X\), we get to expand our variational family to the set of Gaussian mixtures.

At the end of the day, M2 only cares about minimizing the variational loss. So it asks a simple question:

Which is better?

- Have 10 different data-generating manifolds, but a simpler Gaussian variational family.

- Have a single data-generating manifold, but an expanded Gaussian mixture variational family.

It would appear that M2 chose the second option. To really test this hypothesis out, we should use a more expressive variational family and see if \(Y\) remains uninformative about \(X\). I will get round to testing this later :)

M2 Is A GMVAE In Disguise

One thing I did not like about my previous hypothesis was that it felt like a cop-out. I am quite confident that if our variational family is better, \(Y\) would be used. That M2 doesn’t encode into \(Y\) is likely a manifestation of over-pruning and the bits-back coding mechanism.

I wanted to know if there is a simpler way to encourage encoding into \(Y\) while adhering strictly to the variational framework. Simply put, I wanted to demonstrate that the “anti-clustering” prior can be easily overcome without having to tweak our objective function with \(\eta\) or the Consistency Violation term.

It turns out that a simple solution does exist. After some thought, I realized that the M2 model is not just any mixture VAE—it is a Gaussian Mixture VAE! To see this more clearly, we will have to pry open the \(\mu_x(\cdot)\) function.

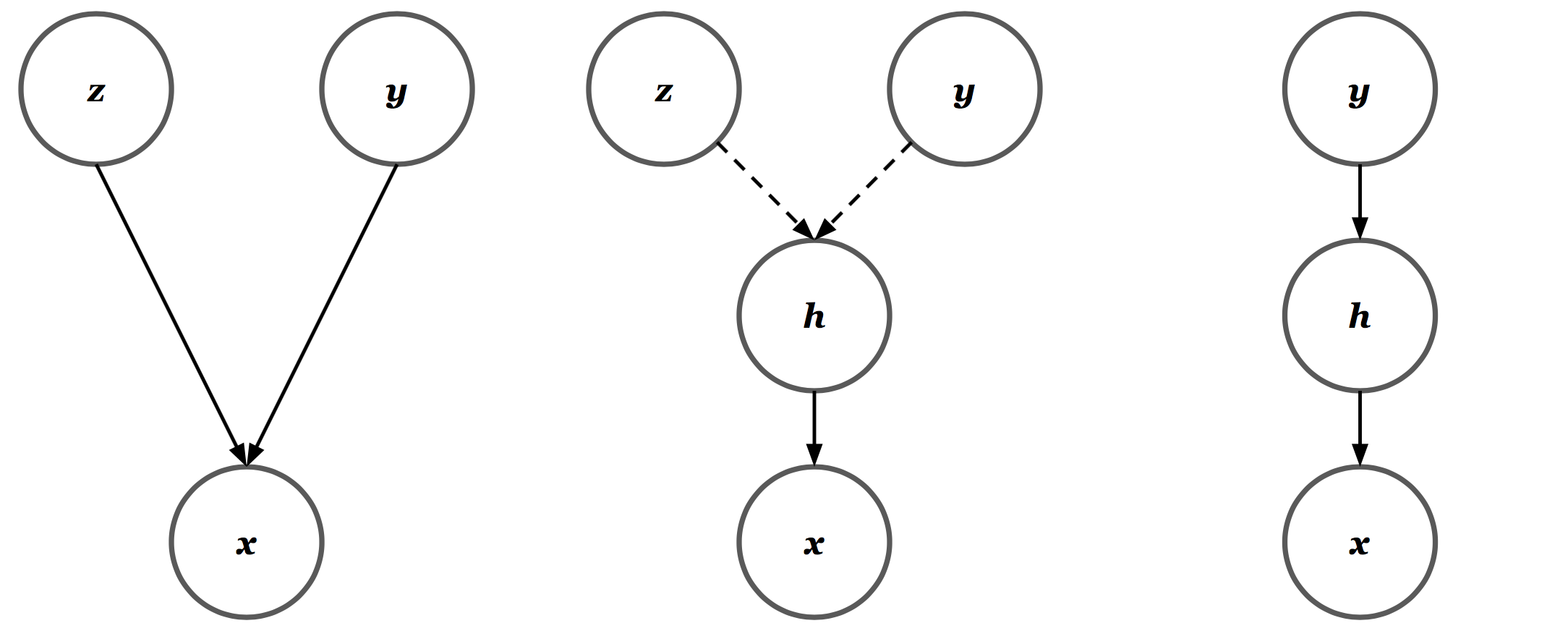

\[\begin{align*} h_1 &= W_y y + W_z z\\ a_1 &= \text{ReLU}(h_1)\\ h_2 &= W_2 a_1 + \beta_2\\ a_2 &= \text{ReLU}(h_1)\\ &~~\vdots \\ \mu_x(y, z) &:= W_n a_{n-1} + \beta_n. \end{align*}\]Note that \(H_1\) is a deterministic function of the random variables \(Z\) and \(Y\). Since \(z\) is drawn from a unit Gaussian and \(y\) is a one-hot vector, we have a mixture of Gaussians in the space of \(H_1\). As a result, it’s not too much of a stretch to claim equivalency between the three Bayesian structures shown below. Out of convenience, I represent the deterministic transformation \(h = W_y y + W_z z\) with dotted arrows. All other arrows represent conditional Gaussian or Bernoulli distributions where appropriate.

There are, however, two set-backs. First, since \(W_z\) is independent of \(Y\), we have a mixture of Gaussians whose components all share the same covariance. And more crucially, even if we force \(W_z\) to be a square matrix, we have no guarantee that it is positive definite. To address both issues, I made a simple change

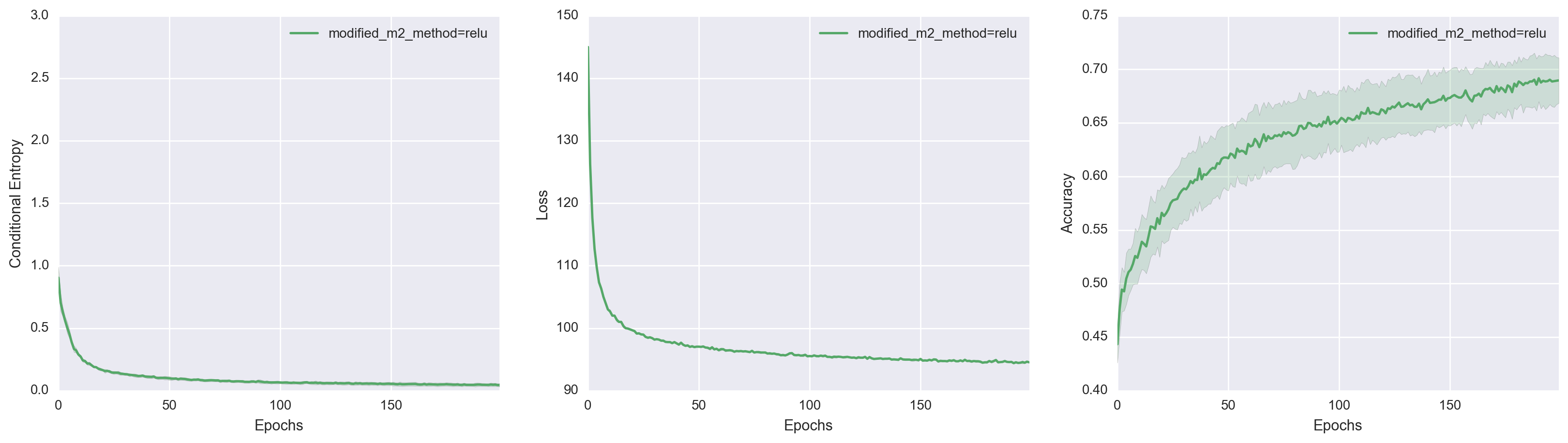

\[\begin{align*} W_z &:= \text{diag}(\sqrt{\text{softplus}(W_s y)}). \end{align*}\]I chose a diagonal structure for simplicity, but the important point is that \(W_z\) is now forced to be positive definite. So let’s see how well this modified version of M2 does.

It turns out this simple change made a huge difference! By explicitly making the transformation matrix positive definite, it’s as if we tied the generative model down and told it

You have to use a non-degenerate mixture of Gaussians or I will cut you

Surprisingly, we made no change to the inference model at all. We simply restricted the generative model to exhibit a specific behavior, which indirectly led to the modified-M2 deciding that having 10 different data-generating manifolds is a good thing.

The Real Gaussian Mixture VAE

One odd behavior I encountered when using the modified-M2 is that the loss would suddenly become NaN after several hundred epochs. I imagine clipping the gradients would prevent this from happening, but it is interesting that this behavior appears at all. I attribute this to optimization challenges associated with the specific way the modified-M2 is trained.

There is something quite awkward about the modified-M2 model training objective. Our actual latent variable of interest is now \(H_1\), which we have forced to be distributed according to a proper mixture of Gaussians. However our inference model never explicitly computes \(q(h_1 \mid x, y)\). Instead, we perform inference on \(Z\), which really only serves as an auxiliary variable for generating \(H_1\). This means we are performing inference on the auxiliary variable used in the reparameterization trick! That can’t be a good thing, can it?

To address this, let’s reorganize our generative model to better reflect that our model contains a single-stochastic layer whose marginal distribution is a mixture of Gaussians. We do so via the following

\[\begin{align*} p(x, y, z) &= p(y)p(z \mid y)p(x \mid z)\\ y &\sim \text{Cat}(1/K) \\ z &\sim \mathcal{N}(\mu_z(y), \sigma_z^2(y))\\ x &\sim \mathcal{B}(\mu_x(z)), \end{align*}\]I stress that our inference model remains exactly the same.

\[q(y, z \mid x) = q(y \mid x) q(z \mid x, y).\]From a computation stand-point the M2, modified-M2, and real GMVAE models use the same inference networks. However, we interpret the GMVAE inference model very differently. In particular, the marginal distribution of \(Z\) is now a mixture of Gaussians, and we use a Gaussian \(q(z \mid x, y)\) to approximate the posterior. Putting everything together, our variational lower bound becomes

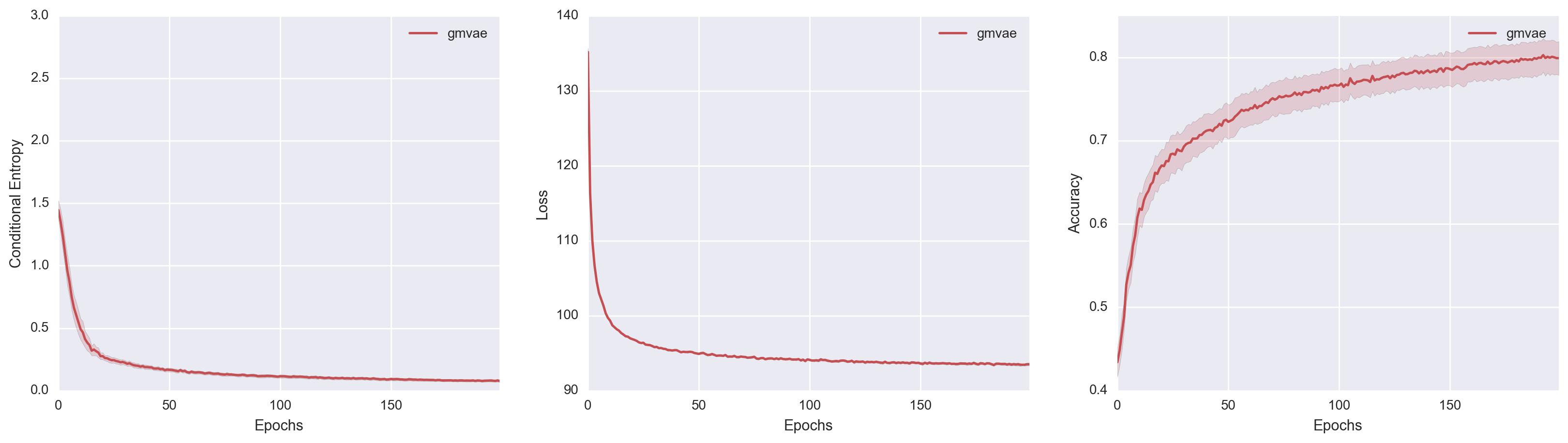

\[\begin{align*} \mathcal{L} &= \E_{q(y, z \mid x)}\brac{\ln p(x, y, z) - \ln q(y, z \mid x)} \\ &= \E_{q(y, z \mid x)}\brac{ \ln \frac{p(y)}{q(y \mid x)} + \ln \frac{p(z \mid y)}{q(z \mid x, y)} + \ln p(x \mid y, z)}. \end{align*}\]I took the liberty of grouping like-terms together. Unlike the modified-M2, signal from the objective function is directly propagated into \(p(z \mid y)\), which hopefully provides a stronger signal for \(Y\) to be informative about \(X\). Using our new-and-improved real GMVAE, I achieved the following results.

The improvement is striking! The real GMVAE with proper inference achieves the best performance out of all three models. I ran the same experiment multiple times. By the 1000th epoch, five out of six replicates achieved accuracy performances above 80%. One of them even achieved an accuracy of 95%! Surprisingly, our real GMVAE managed to outperform the “GMVAE(M=1) K=10” model both in terms of best run and average run (and does about as well as the “GMVAE(M=10) K=10” model). Also, in constrast to the models from the paper, I didn’t have to rely on convolutional layers, Consistency Violation, or \(\eta\), which I consider a personal victory. *blows knuckles*

To get a better comparison of the models, I also superimposed all three model performances. In doing so, we actually get to see something pretty interesting. If we look at the middle Variational Loss v. Epochs plot, M2 achieves the best loss value despite its poor clustering ability. Modified-M2, on the other hand, has a constrained generative model which led to higher variational loss but better clustering. While not definitive, I think this lends further credence to the hypothesis that M2 chooses a Gaussian Mixture variational family over a Gaussian Mixture manifold because the former leads to lower variational loss.

Final Remarks

These experiments helped me get a better understanding of what’s going on behind the scenes of deep generative models that use variational inference. Making these tiny tweaks only to the generative model and arriving at vastly different model behaviors speaks volumes about the importance of really grokking deep generative models and deep amortized variational inference.

If we really only cared about building a deep generative model, we probably won’t care much about whether certain latent variables are being pruned so long as we get a good log-likelihood score. However, if the plan is to repurpose the inference model for a downstream task such as classification or interpretable representations, we should pay more attention to how we set up both the inference and generative models. On that note, I think there is still value in the Consistency Violation term because it gives us explicit control over what the generative model is doing. We can think of CV almost like a prior imposed on the behavior of the generative model, and I imagine it being very valuable once we move to deeper DLGMs or more mixture components. I would also not be surprised if applying CV to the real GMVAE leads to even better clustering performance.

But hopefully, I’ll never see a term like \(\eta\) ever again. Because I think there are definitely more elegant and insightful ways of getting the generative model to do what we want.

Wait, what’s this paper? A \(\beta\) term…? (╯°□°)╯︵ ┻━┻